With the birth of the Renaissance, European intellectuals and artists increasingly sought to revive the wisdom of classical antiquity. While this story of the renaissance, literally meaning "rebirth," is likely familiar to most people, what's often left out from the narrative told by historians of "high culture" is that there was a revival of the military traditions of antiquity. Polybius, the famous Greek historian of Rome, was one classical writer who was rediscovered in this period. Initially, men such as Niccolo Macchiavelli showed interest in Polybius' political philosophy (as evidenced in Discourses on Livy), but by the late 16th century, more and more writers became interested in Polybius' digressions into Rome's military organization and tactics. This desire was likely fuelled in part by the looming Ottoman threat over Europe, but also the rapidly expanding scale of warfare and hot-spots of almost ceaseless military conflicts (ex. Northern Italy) fought by mercenary armies who could be unreliable at the most critical moments.

For late 16th century European writers, familiar with how fickle mercenaries could be, the highly organized and professional nature of classical Roman and Greek armies was an exemplary model worthy of being revived. For example, in De Militia Romana, Justus Lipsius' translation and commentary of Polybius' writings on the Roman army, Lipsius had the following to say about the lack of military discipline in his time:

Whichever way one esteems the discipline of the Ancients, now there is none at all, as the very soldiers will acknowledge. O shame! O dishonour! Even barbarians and Scythians outdo us in this aspect, for at least, they have some kind of standards; we have none!

The drum sounds: they assemble, have their name put in the musterbooks, they make a few changes to their attire, assume a forbidding look, play the ruffians and lose themselves in boozing: here comes the army! (translation taken from chapter 6 of Recreating Ancient History: Episodes from the Greek & Roman Past in the Arts & Literature)And it was amidst these calls for a revival of military discipline and translation of classical military treatises that one of the most important innovations in early modern warfare was invented by former Leiden University students of Lipsius. I'm of course referring to Willem Lodewijk and Maurice of Nassau's development of the volley-fire countermarch. Now there are several points that I wish to clear up (despite having no academic credentials) just because there seems to be a lot of confusion regarding the terminology and development.

|

| Crossbow volley-fire |

see this video), and as guns became lighter, faster, and possible to reload easily while kneeling, it became rather pointless to physically have men at the front line march to the back. It was much faster to just keep men fixed in their positions and keep firing away by either ranks or platoons.

The second and more important point I want to bring up is how Willem Lodewijk and his cousin, Maurice of Nassau, came to develop the volley-fire and countermarch. There seems to be a popular notion that they were inspired by Roman troops using the countermarch to deliver volleys of javelins, and this is the version you find in this wikpedia page. This is likely wrong because Willem, the one who came up with the idea of applying countermarches to musketeers, was inspired by the Aelianus Tacticus, a military treatise about Hellenistic army tactics and drill, not Roman drills. In contrast, Maurice was the one who preferred learning from the Roman army, hence his adaptation of the Roman maniples. Another reason why it's wrong is that when Aelian discusses countermarching, it's a drill meant for melee heavy infantry (phalangites and hoplites), not missile troops. I'm pretty sure there's no mention anywhere about volley-fire or countermarches for javeliners, slingers, or archers. This might seem odd to you if you've only ever seen countermarching within the context of volley-firing crossbowmen or musketeers. But the countermarching that military officers of antiquity were more concerned with was like this video already linked, which is all about getting a formation of troops to face another direction while still maintaining the same order.

|

| Macedonian phalanxes countermarching before battle |

My point here with this example is that while military reformers such as Willem Lodewijk and Maurice of Nassau are sometimes thought of simply reviving the lost art of Greek and Roman military drill, but they deserve more credit than that. They ignored Lipsius' suggestion early modern European armies to give up their guns and fight as the Romans did. They also ignored those scholars who argued that the advent of gunpowder invalidated all Roman precedents and that there was nothing applicable from classical military texts. Instead, they sought to take contemporary context within mind as they reinterpreted and borrowed the wisdom of antiquity, resulting in a final product that was quite different from the original. Their version of the countermarch that helped revolutionize early modern European warfare was not something that Roman and Greek armies would have recognized. Rather than being a heavy-infantry maneuver to be used before the actual fighting, the Dutch countermarching volley-fire was a missile-infantry manuever to be used during fighting.

Fuck, I now realize I spent over a thousand words in a throwaway example from military history, so let me finally get to what I originally intended to talk about: Confucian economic thought.

|

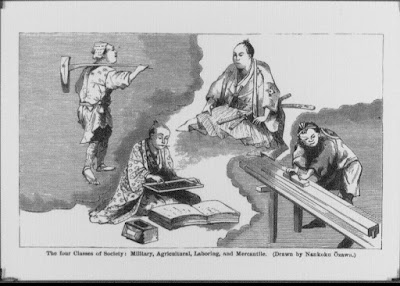

| Ideal four-class Confucian social structure as envisioned in early modern Japan |

|

| On an unrelated note, as a guy not too interested by metaphysical philosophy, Neo-Confucianism is a little "too much" for my liking. |

|

| No offense, Wang Yangming, but your hat looks like there's a red dick flying out from it. |

|

| Google Noguchi Tetsuya if you haven't heard of him. |

It is efficient to look at the root of things. Why are rice fields delivered to farmers and rice is paid by them? What is the logic to take rice from farmers? . . . All things between heaven and earth are goods, including rice fields, mountains, seas, money and rice. It is a principle that goods repeatedly give birth to goods. That rice fields give birth to rice is no different from money yielding interest. It is the principle of the universe that mountains give birth to wood, that seas contain fish and salt, and that money or rice yields interest. Rice fields produce nothing if left unattended. Money yields nothing if set aside. Rice fields are lent to farmers, and a ten percent land tax is paid by them. This is the same as collecting ten percent interest. . . . Taxes on rice fields, mountains and the sea are the same as interest. Taxation is the equivalent of lending goods and taking interest. It is natural that interest must be taken. . . . It is the principle of the universe. . . . This is the situation with lower-status merchants, and it is not bad. From the earliest times, it has been said that the relations between lord and retainer conform to the way of the market (shidō 市道). A lord lets a retainer work by giving him an annual stipend, and a retainer obtains rice by selling his own power to a lord. A lord buys a retainer and a retainer sells oneself to a lord. That is just buying and selling. Buying and selling is good.For people unfamiliar with Neo-Confucianism, "principle" isn't some word you just throw around. Principle (理, Ch. li; Jpn. ri; Kor. yi) is a metaphysical term that more or less refers to the inherent order that makes up the universe and every thing that exists within it. It's a term of vital importance in the entire philosophy of Neo-Confucianism. So for a guy to use Principle itself to justify the pursuit of economic profit is like... I dunno, maybe like a Christian theologian using the concept of trinity to justify usury? It's fucking insane! But that's my whole point here. Sometimes, we tend to think of pre-modern people as being highly traditionalist. This static view is (or maybe, was) especially prominent in Western views of non-Western cultures. But believe it or not, even people back then had a way of tinkering around with the so-called "hallowed Antiquity whose ideas and traditions must not be changed." Hell, even that OG-mofo known as Confucius said he came to "restore tradition (fuli)" but surprise, surprise, he actually added a whole shit-ton of innovations to the ancient Zhou rituals.

While I've so far been drawing examples almost exclusively from the early modern era, I do want to point out that this refashioning of Antiquity to either intentionally or unintentionally approach modernity was quite important in the modern era especially for non-Western cultures threatened by Western imperialism. For many non-Westerners, a choice had to be made: to admit the incompatibility of Western and native traditions and thus make a mutually exclusionary choice, or to "discover" their compatibility. To better demonstrate this idea, let me draw a few examples from the Middle-East. In the 19th century, many Islamic intellectuals fiercely debated whether or not things like Western science, democracy, or banking practices could be adopted without violating Islamic law. For some reformers, the threatened state of the Islamic Ummah meant that one shouldn't be too afraid of breaking some aspects of traditional Islamic law. Some of the more radical reformers ended up losing faith in Islam and became apostates while others remained religious but supported secularism in governments. But either way, these reformers often hit a brick wall because their willingness to "bend" certain Islamic traditions meant their ideas lacked legitimacy. And it's this issue of legitimacy that the movement of Islamic Modernism attempted to solve. Basically, these guys went back to the foundation and came up with elaborate ways to make modern Western institutional practices compatible with the Islamic tradition. For instance, some saw in the idealized and "pure" world of early Islam, practices that could justify socialism or communism. Others revived the use of ijtihad, something that had gone mostly out of practice in Sunni Islam, to justify adoption of things like Western science or legal reform borrowing from Western models (side note: ijtihad is the Islamic legal term to describe the process of a jurist to make an appropriate legal decision by using independent reasoning for cases when neither the Quran nor the Sunnah provided a ready-made solution).

But I think the most interesting example comes from Iran. Whereas many Arab intellectuals sought for solutions in the idealized and partly imagined nature of the Islamic Golden Age, Iranians were reminded by European archaeologists that there had once been a mighty Iranian empire long before the advent of Islam. When combined with the Aryan master race theory, it became natural for some Iranians to conclude that Iran's weakness in the modern-age was a consequence of the brutish Arab yoke repressing Iranian/Aryan ingenuity during the Islamic conquests. This rise of anti-Arab sentiment, especially among Iranian reformers, was thus accompanied by a glorification of Iranian Antiquity, something perhaps best encapsulated by the following quote from Hassan Taqizadeh, a prominent Iranian politician: "Iranians must become aware of their ancient culture and their thinkers, artists, and kings so that they will be aware of their great nation in the past before Islam and of what race they derived from, how they have reached their current condition, and how to regain their original greatness as a nation."

Naturally, it was impossible to envision pre-Islamic Iran without bringing up Zoroastrianism. And so, what resulted was this bizarre imprinting of modernity onto Zoroastrianism. That is to say, the legitimacy problem I mentioned previously was solved by anachronistically projecting modern ideals of rationalism, science, hygiene, and even women's rights onto Zoroastrianism. As such, Zoroastrianism became so distorted that rather than being an actual religion, it became re-imagined as a secular tradition accessible to all Iranians and thus not mutually exclusive with Islam. This seems to have reached a peak in the years of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1979) when there was heavy state support of Zoroastrianism and all things pre-Islamic Iran. For instance, Zoroastrians in Indians were asked to come and revive the Zoroastrian tradition in Iran. Another more famous example is the claim that the Cyrus cylinder was "the world's first charter of human rights," which is nowadays often dismissed as mere hyperbole. Of course, with the 1979 Iranian Revolution, there was a sharp turn-around, but even today, the grandeur of Iranian Antiquity lingers on to be periodically invoked by hopeful reformers (for example, see this paper).

Alright, that's enough rambling for one post. I hope you found some of these examples as interesting as I did when I first learned about them.

I enjoy reading your history (also news and manga) posts but as someone who knows dick about history despite having an interest in it, I typically don't have much to say except ⊙△⊙ (I also have a lot of problems commenting through blogspot)

ReplyDeleteHowever, I chose to brave the captcha hell to support re-examining the ancient wisdom of Wang Yangming's hat.

No need for a witty or insightful comment. Just seeing that there are people who actually read through my several thousand word-post on history is enough to make me happy.

Delete